A Senior Exploration into Dr. Arnold Gesell and the Yale Clinic of Child Development

Sarah*, a recent graduate, details her research on the eugenic origins of child development at Yale– through a focus on Dr. Arnold Gesell and the Yale Clinic of Child Development.

*Sarah Laufenberg ‘23 (she/her) is a recent graduate of Yale University with a BA in the History of Science, Medicine, and Public Health.

Hi everyone, I’m Sarah, and I’m going to share a bit about my thesis work! My full thesis is 12,658 words and around 60 pages, which I think renders it a bit inaccessible, so I’m hoping to synthesize some of what I found, talk about disciplinary implications, and highlight my hopes for future work.

Scroll to the end for links to related senior projects, primary sources on Gesell and the Clinic, archives I used, and relevant secondary sources.

My Thesis: How Science Studies the Child

My thesis is entitled, “‘How Science Studies the Child’: Arnold Gesell and The Eugenic Origins of Child Development at Yale, 1911-1948.” Find the full version here.

My title is derived from the title and subject of a 1932 radio talk, “How Science Studies the Child: A Science Service Radio Talk” by Gesell, found in the Library of Congress (LOC) Arnold Gesell Papers, 1870-1971. Coincidentally, 1932 is the same year a membership card signed by Harry Laughlin indicated Gesell’s Active Member status for the Third International Congress of Eugenics.

A membership card for the Third International Congress of Eugenics, in the name of Arnold Gesell. It is signed by The Third Congress secretary and superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office (1910-1939), Harry H. Laughlin.

(Source: The LOC Arnold Gesell papers, 1870-1971)

In this 1932 radio talk, he narrates how science can actually guide social welfare, how improving the mental faculties of the child- and measuring them through ‘objective’ observation- was a matter of culture protection and survival.

I found this historical lens of reflection– looking at how Gesell himself asserted the centrality of his work and innovations, the cutting-edge of his science, and the narration of the development of an emergent field– to be the most important guide to my historicization of eugenics in child development at Yale. And by the early 1930s, the scientific study of child development was expanding at a very rapid rate, according to Gesell. The following is a quote from the radio talk script on the social implications of a child study:

“If scientific progress continues at the present rate, it will be possible for later generations to detect individual variations from the normal at very early ages. That will lead to prevention and cure of many behavior disorders. It may some time [sic] also be possible to discover gifted individuals of the community in the cradle and the nursery. Indeed, it will become necessary for future society to greatly perfect the education of all children in the first fundamental years of life. Science alone can determine the scope and the hygiene of that fundamental education.”

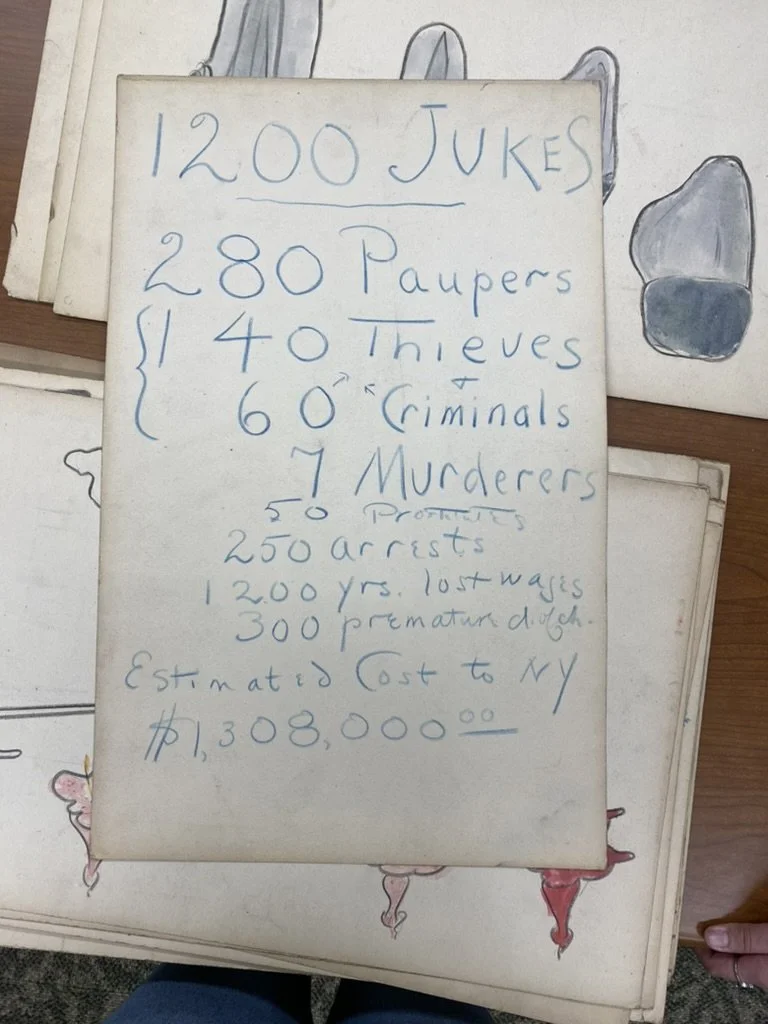

Using Gesell’s own framing of the field of child development, I sought to examine how science came to study the child, and how the technologies and structural frameworks of the field were undergirded by ideas of fitness and reactions to perceived social crises (including poverty, criminality, and juvenile delinquency). Eugenic logics masqueraded as “objective” and “benevolent” knowledge production to undergird the clinical study parameters and interventions developed at the Yale Clinic of Child Development.

The logics of his work maintained and produced frameworks upholding eugenic ideas of hierarchy and classification, while producing the infant as a subject and a social problem. In my thesis, I lay out Gesell’s publications, letters, and notes to demonstrate the ways in which eugenic modes of differentiation became integral to clinical practice and developmental paradigms.

Gesell and the Early Clinic Years

In 1911, newly-hired Professor of Education Arnold Gesell implored the Yale School of Medicine’s Dean, George Blumer, for the space to open up a new, unique kind of study. The Juvenile Psycho-Clinic was born of calls for examination and intervention for “backward and defective children” in Connecticut public schools. It started as a single room in the New Haven Dispensary. The Psycho Clinic, which would ultimately become the Child Study Center, was the praised site of Gesell’s long-standing contributions to producing knowledge about child psychology, pediatrics, and hygiene.

Arnold Gesell spent the first five summers (1911-15) since the Clinic’s inception teaching “special class teachers” of “retarded children” and conducting research at Vineland Training School in New Jersey alongside his good personal friend and colleague, Henry Goddard.

Psychologist Henry Goddard (1866-1957) adapted the Binet intelligence test to the United States in 1908, administering it on his patients at Vineland to classify them by their mental age and to investigate the Mendelian inheritance of feeblemindedness. Goddard coined the term ‘moron’ to refer to a discrete classification of persons who could pass under the radar of normalcy but were still deemed a threat due to their inherent mental deficiency.

Gesell’s contemporaries created a discursive terrain of vocabulary and frameworks which produced, defined, and validated difference. And the value of those cast out by this stratification clearly lay in their role in academic and institutional productions of experimental and clinical knowledge. We can gather that his time researching and learning at Vineland informed his clinical work and examinations of children labeled and being categorized as deficient.

In 1913, 2 years after the Clinic’s founding, Gesell penned “The Village of a Thousand Souls” in The American Magazine.

“Eugenic map of The Village of a Thousand Souls—220 families (1880-1913)”

Gesell’s mapping of degeneracy and his graphic metaphors of community contamination pushed the reader to formulate and imagine their own visceral disgust towards the ‘symptoms’ of social crises otherwise hidden amidst “ordinary village humanity.”

The above illustration is a eugenic map of Gesell’s village survey. The absence of one of the eight possible symbols (representing Feeble-minded, Insane, Suicide, Alcoholic, Epileptic, Criminal, Eccentric, and Tubercular) indicated a “normal” family. (Source: The American Magazine)

I found the draft eugenic map for this article within the LOC collection, in a folder containing multitudes of other kinds of visualizations of heredity, pedigrees, and, family charts. A nuanced and visual understanding of eugenics was key to his approach to his work at the Clinic of Child Development as well, in how he presented his ‘empirical’ observations of the constructed categories of normalcy and defect in infant children.

(Source: The LOC Arnold Gesell papers, 1870-1971)

The Clinic of Child Development

Arnold Gesell was not single-handedly producing eugenically-aligned modes of thinking, but he was digesting and reproducing them at the site of legitimization that he created, the Clinic of Child Development.

The initial purposes of the Clinic were to “determine the mental status and capacity of subnormal or otherwise exceptional pupils of the public schools” and “to collect and file data in regard to mentally and morally exceptionally children”. In sum, the Clinic functionally served as a facilitator of isolating difference, providing recommendations for intervention, and aggregating the subnormal individual into a collectively scaled social trend or problem.

The Clinic served as a theoretical laboratory as well, in the sense that it workshopped new conceptions of public health. In trying out new modes of observation and classification, clinical care interacted with social control and modes of mental and physical hygiene. Such was the case with the New Haven Hospital’s Well Baby Conference (beginning in 1932). Aligning with the Clinic’s capacity to provide the medical teaching and learning apparatus for the University, the Well Baby Conference gave opportunity to focus examination and inquiry on the level of the infant. From the period of November 30, 1932, through July 1934, 100 infants under six months of age were subjected to repeated examination beyond their typical level of required care at the New Haven Hospital Dispensary. A summary of YCCD appointments from 1934 through 1935 indicate that Gesell looked for special research or clinical features, and classified children according to mental status (superior, average, borderline, or defective), guidance problems (such as general guidance, parent-child relation, masturbation, temper, social adjustment, and “defective child”), social factors (including adoption, institutional environment, dependent child, heredity, illegitimate), and even more dimensions of cataloging.

Gesell’s investment in visual technology for research and intervention reflected how these devices were central to knowledge formation at the Clinic of Child Development. His innovative observational technologies, like one-way viewing screens and the Gesell Observation Dome, as well as cataloguing technologies, like photographic sequences of growth, and motion picture compilations, contributed to the visual isolation and targeting of characteristics indicating normality or defect.

These technologies, like the eugenic charts, pedigrees, and diagrams, presented normalcy and deviancy as discernible and legible to a commonsense notion of eugenic hierarchy

Yale as a Nexus of Eugenic Knowledge Production

Eugenics “moved into the universities and there formed the basis for research in a variety of fields” by way of hereditarian ideas about intelligence, propagation, and human fitness.

While Yale University was fostering its elite reputation as a rigorous research center in the 1920s and 1930s, it was simultaneously becoming a locus of eugenic knowledge production. The Clinic operated during a time that administrators, faculty, and alumni were producing eugenic knowledge and acting on foundational beliefs about fitness and hierarchy.

More context can be found in the extended thesis, throughout our website, and in Dora and Emme’s theses, linked at the bottom of the page.

Science and Service

Gesell was deeply invested in classification and measurement to record “the radical inequalities which naturally exist between children.” Gesell naturalized difference in his subjects— transforming it into something not socially produced, but innate and to an extent, self-evident. He formulated through his maturational theory that “in a psychobiological sense, problems of human personality have a genetic or developmental aspect which traces back to infancy.”

The clinical laboratory became a site of revelation for the fundamental laws of growth, so that public health reform could apply scientific lessons. From this perspective, child study could be considered a science of human welfare—one that improved the infant’s life, but more so the population at large whose collective mental and physical health were being measured, guided, and treated.

Solutions oriented to the individual infant could be harnessed as public health intervention through a preventative social hygiene approach. Modern public health practice constituted prevention and the need to anticipate when an individual would grow up to be a burden to society. As such, the core value behind Gesell’s imposition of a public health approach to his new field of scientific study was an institutional commitment to bettering the nation and the race by pursuing science

Contemporary Memorializations + Disciplinary Implications

While his exact developmental schedules and maturational theory have been discounted, a notion of internally-guided individual development undergirds ideas of developmental progression and abnormality more generally. The paradigms of development may not be currently in use by experts in the field, but the underlying philosophy of growth that they propped up was fundamental to child study as a concept and undergirds conceptions of development today. As of July 2018, the National Association for the Education of Young Children ‘proudly’ displayed their reliance on Gesell’s enduring contributions to thefield of child development and differentiated instruction (special education), stating, “the norms Gesell established are still used today by psychologists, educators, and pediatricians to predict developmental changes (and to note when follow-up evaluations of development may be warranted)”.

The contemporary Yale Child Study Center, looking back on 100 years of research, distances Gesell’s criticism and child development with just a brief phrase: “Although some of Gesell’s views have fallen out of favor, he exerted a strong influence on American psychology in general as well as on childrearing practices.” His specific views that ‘fell out of favor’ remain unmentioned next to the glowing remarks about his influence.

Can we discern the eugenic from the non-eugenic parts of his work and praxis? Is this even possible? The eugenic origins of the disciplines and knowledge production at Yale have influenced the way that power, classification, and method operate in the University today. This project fits into a broader interrogation of what it means for the foundations of an academic discipline to be founded on eugenic grounds or initiated by eugenicist thought. How do we grapple with these histories, and how do they remain embedded even as explicit eugenic language seems to disappear?

One of my most peers, Akio Tamura-Ho, describes in their History of Science, Medicine, and Public Health thesis that histories can be ‘haunting’ in that new knowledges are plagued by historical lineages and the apparitions of larger power structures. With such an understanding, we can imagine the underlying ideology of eugenics as haunting the academic disciplines, institutions like Yale, and our common sense through carceral logics, typology, and social hierarchy. Contextualizing the history of eugenics is one step to validating contemporary criticisms of fields like genetics and psychiatry.

On Future Research

Considering how knowledge production in Gesell’s Clinic reflected knowledge production in the University at large, it is necessary to interrogate how logics of eugenics are reproduced in tools of clinical observation, intelligence testing, and other aspects of the field of child development. Once you see eugenics as a framework, you can begin to see how its logics inform and structure all different domains and ways of seeing people, their value, and their qualities. This can be seen across the disciplines within and also outside our institution, in how knowledge production operates and is legitimated. There is so much more to think about with disciplinary origins.

With child development in particular, a more critical look at key visual, observational, and theoretical technologies is important. And scholars like PhD Student Kelsey Henry are historicizing the “production of developmental technologies and norms that are often perceived as race-neutral, like pediatric growth charts and developmental screening tests, interrogating the racial premises and parameters of developmental knowledge production and its material effects on black life.”

If ever you want to get in touch about the work, to share reactions or stories, feel free to get in touch through Professor HoSang!

Links that Might be Helpful

Related theses projects:

Read more about the Clinic and its Impact here:

“Child Development: Arnold Gesell has made its study into a whole new science” in LIFE magazine (Apr 1947)

"Child Study Center: Mission & History." Yale School of Medicine.

Chapter “Out of Step with His Times: Arnold Gesell and the Yale Clinic” of Alice Boardman Smuts’ Science in the Service of Children, 1893–1935. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,

2006).

Archives I used:

Yale Child Study Center reference collection

Arnold Gesell and Colleagues Publications collection (at Yale)

Library of Congress Arnold Gesell Papers, 1870-1871