It is common for new residents at the School of Medicine to join walking tours of New Haven to familiarize themselves with the area. However, the AECY and collaborators created this tour to, rather than use New Haven as the object of interest, cast our view back at Yale and its legacies of eugenics.

Click through our tour below

The first stop of the tour was the New Haven Green, which is also home to the original headquarters of the American Eugenics Society (AES), which stands just left of where the New Haven City Hall currently stands. Much of the Yale Faculty was involved in the activities of the American Eugenics Society, which included fitter family and better baby contests, eugenic sermon contests, advocacy for restrictive immigration and sterilization, hosting of lectures, and recruitment of leading scholars, scientists, and administrators to popularize Eugenics across every part of the country.

The second stop of the tour was Jonathon Edwards College, one of the residential colleges for undergraduates at Yale University. The college is named after Jonathon Edwards, who graduated from Yale in 1720. For eugenicists, Edwards epitomized a eugenically ideal family line. Eugenicists created pedigree maps that purported to track traits of Edwards and his descendants as evidence that intelligence and other qualities were inherited and contrasted them with “inferior” family lines, such as the Jukes and Kallikak families who were said to have high rates of criminality and delinquency. Jonathon Edwards (JE) College sits on the former site of the Institute of Psychology (1924-1929). Funded by the Rockefeller family, the Institute hired leading faculty in the American Eugenics movement, integrating experimental psychology and hereditarian ideals. These figures included Robert Yerkes, who developed and advocated for intelligence testing to be used to limit immigration into the United States. The building was razed to make way for JE College, which opened in 1933, part of a major expansion of the university’s footprint. Even by the late 1920s, there were growing concerns in New Haven about the university’s acquisition of land and its impact on the city’s tax roll.

The third stop was the Oak Street Connector. Here, New Haven’s urban redevelopment project in the 1950s displaced hundreds of residents in the Oak Street community of downtown New Haven to construct a freeway, now known as the Oak Street Connector or Richard C. Lee Highway. Constructed under the administration of Mayor Richard C. Lee, the Oak Street Connector represented the culmination of New Haven’s interest in the “regeneration” of a city undergoing “degeneration.” Specifically, the freeway was designed to manage the traffic flow of cars into and across a city experiencing white flight, Eugenicists had long argued that integrated, working-class neighborhoods like Oak Street were themselves “dysgenic” and produced “socially inadequate” people. In 1913, for example, Dr. Arnold Gesell, founder of the Yale Child Study Center, published a study on his hometown in Wisconsin titled, “The Village of a Thousand Souls,” in which he argued that houses of the “feeble mind” and the “vigorous mind” were visually distinct, labeling particular houses “feeble-minded,” “Insane,” “Criminal” and “Tubercular." The City failed to relocate thousands of residents whose homes were demolished. Today 55% of New Haven’s real estate is exempt from property taxes, including $4.3 billion owned by Yale and Yale-New Haven Hospital, which are tax-exempt.

The fourth stop of the tour was 333 Cedar St, the home to the Institute of Human Relations (IHR). The IHR marked a great expansion of Yale as a research university. Eugenicists were cheered by the IHR, not that “although not specifically an institution devoted to eugenical research… friends of eugenics must have been fascinated by the reports in the press within the past few weeks of the great new Human Relations Group which is taking form at Yale.” In a 1929 letter from Yale President James Angell to Yale alum and Eugenics supporter Edward Curtis stated that “large parts of the program of the new Insitute [for Human Relations] are in effect in the field of Eugenics, although not carrying this name.” The Institute contained laboratories for the study of child development, “mental efficiency,” and other psychological investigations. Yale unveiled the Institute to “achieve a better understanding of human nature and the social order and to correlate knowledge and coordinate techniques in related fields to make greater progress in the understanding of human life from the biological, psychological, and sociological points of view.” The construction of the IHR in 1929 displaced numerous residents and businesses on Park Street, Howard Avenue, and Davenport Avenue. Gesell’s Clinic of Child Development housed rooms for observation, examination, interviews, and a “photographic laboratory.” The researchers equipped the space with one-way mirrors, allowing researchers and parents to observe child behavior while preserving “the naturalness and spontaneity” of the child’s actions. Researchers photographed children and their behaviors at monthly intervals, creating a chart of their mental growth along a standardized curve.

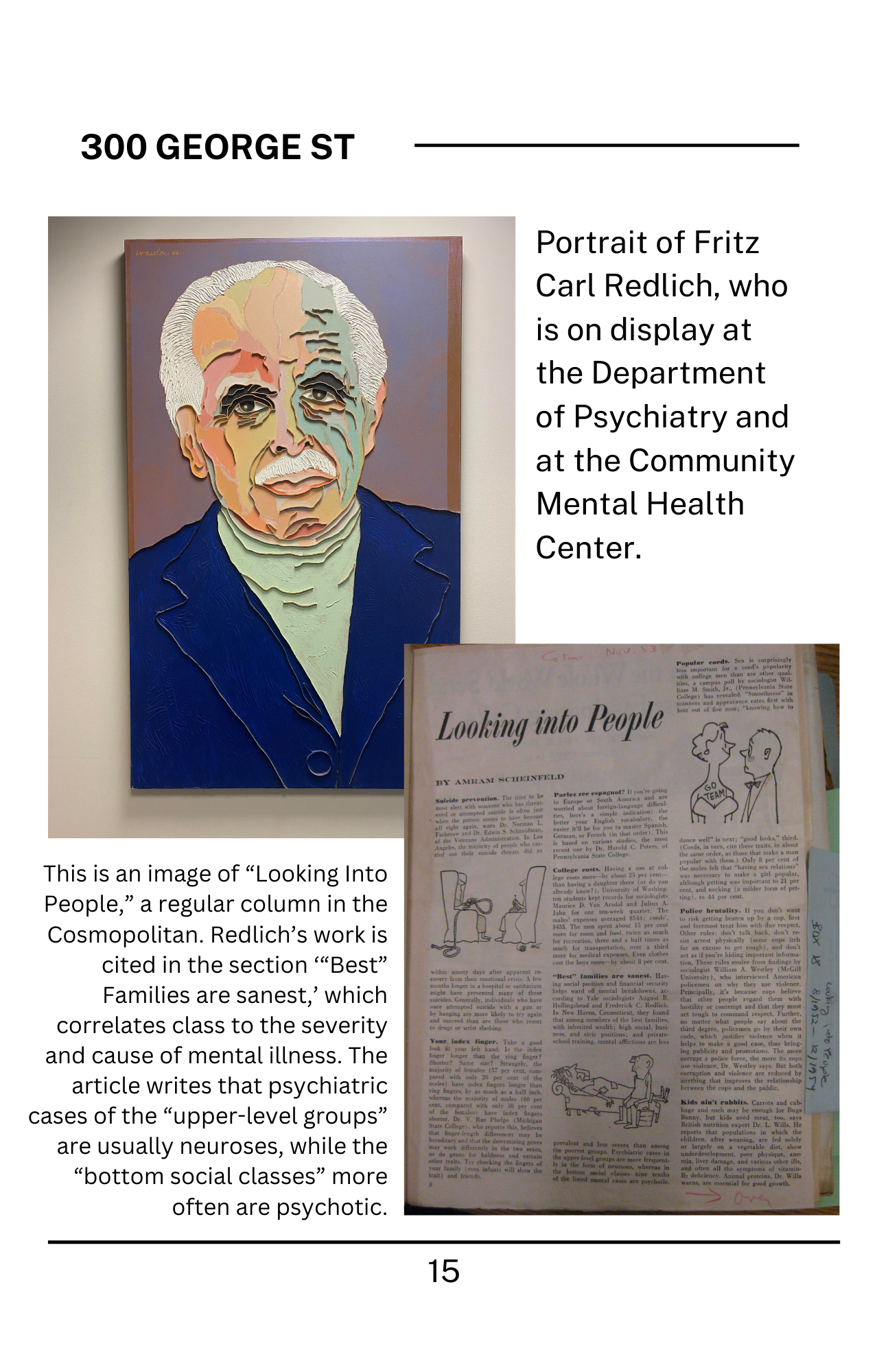

The final stop is 300 George Street, where the Yale School of Medicine Psychiatry Department is. Here, Our tour calls attention to Fritz Carl Redlich (1910–2004), whose portrait is showcased on the wall of the department room. Dr. Redlich was an academic psychiatrist who served as Chair of the Department of Psychiatry (1950 to 1967), the first Director of CMHC (1964), and Dean of the Yale School of Medicine (1950 to 1967). Dr. Redlich is most famous for his contributions to community mental health published in 1958 (with Yale sociologist August Hollingshead) in the award-winning book Social Class and Mental Illness. The book divides New Haven into five racialized “classes.” Redlich asserted that Class I individuals were wealthy, educated, and could trace their lineage back to the first White settlers in New England. Class V individuals were African American or immigrants and described as unemployed, uneducated, poor, and at times, unhoused. Redlich and Hollingshead argued that psychiatrists must approach these classes of people differently in terms of formulation and treatment. Lower-class children, for example, were seen as more likely to have a “defective superego.” Since Redlich argued that class V adults were inclined to physical violence, the instance of a class I husband beating his wife should be “evaluated quite differently from similar occurrences in class V,” according to the authors.